Sailing uses the energy from the wind to propel the yacht through the water. In order to navigate towards our destinations, we need to know which direction the wind is coming from so we can plot our appropriate course.

There are various different ways to tell wind direction, some use fancy gadgets, others do not. The most common gadgets to detect wind directions are:

Electronic Masthead Wind Sensors

Windex

The other end of the spectrum does not involved fancy gadgets or instruments:

A wet finger

Wind on your face

Tuft of yarn or line

Reading the sails

Reading the waves

Lets begin with the fancy gadgets, as they are usually marketed as "Must Haves". Electronic Masthead Wind Sensors are simply a wind vane connected to a potentiometer. As the wind vane turns to point into the wind, its position is converted into an electrical signal which is then displayed on a gauge in the cockpit. These gauges can be as simple as a needle pointing the wind direction over an illustration of the vessel, or a digital screen that calculates true wind and apparent wind direction. These instruments will take all the guess work out of sailing, telling you exactly where the wind is coming from in relation to your boat. Sailing to windward is a matter of looking at the screen to see where the wind is coming from and setting your course to the appropriate wind angle for your boat.

The alternative to an electronic instrument is a device known as a Windex. This highly sensitive device works via the same principle as the wind point, but without the added complexity of electronics. Many boats actually use both, the wind point mounted on the front of the mast, and the Windex mounted on the back of the mast. This provides a wonderful mechanical backup in the event that your electronic unit were to fail. Windex has a wind vane with high visibility paint on the boxes and the wind vane. This allows you to see where the wind is coming from without any guesswork.

Both of these instruments work wonderfully, but they have their pitfalls. Electronic sensors will be exposed to the elements and will eventually fail. This is why the combination of wind point and Windex is so popular. Windex has the pitfall that you have to look at the masthead to read it. If you have a stiff neck, looking up can be quite the chore; if you have a bimini, you will need a window cut in it to allow visualization of the masthead from the helm.

Worst case scenario, you are in a storm and the masthead sensors get blown off. Now there is nothing to tell you where the wind is blowing from! Truth be told, sailing is much older than masthead sensors. This brings us to the "other ways" to figure out the wind direction.

One of the easiest ways to tell wind direction is to wet your finger and hold it up! The side of your finger that faces the wind will dry faster and feel cold compared to the rest of your finger. The cold side faces the wind.

The next way to figure out which way the wind is coming from is to stand up and turn around. As you turn around, you will be able to feel the wind hitting your face and you will know when you are face into the wind. When you find the wind hitting your face head on, you will have a rough idea of where the wind is blowing from. To fine tune your wind reading, you will need to rely on your ears. If the wind is hitting you more from the left side, your left ear will hear more wind noise than your right ear. Turning your head to the left a bit until the wind noise between your ears evens out will fine tune the wind detection. When you hear the same amount of wind noise in your left and right ears, you know for certain that you are facing directly into the wind. While this sounds simple enough, it doesn't work if you are behind a dodger or a lee cloth. If you find yourself behind a wind block, you will have to move to a clear area where you can feel unobstructed wind on your face.

While the first two options listed involve using your body as the sensor, this next one does not. It involves tying a small strand of yarn to various places on the boat. Common places are the shrouds, lifelines, and the backstay. The yarn will stream in the wind and point out the winds direction. This option is very inexpensive, which is why some people will place them everywhere! Instead of yarn, I use bits of line tied to the lifelines. I tie them with a larkshead knot in places where I typically need a bit of line to tie up random things on deck. They are very small and don't stand out as much as a brightly colored bit of yarn, making them less noticeable from passing yachts; but I know where to look for them so I can read the wind from them.

The first three methods will help you figure out where the wind is coming from so you can start moving, the next method will help while you are already sailing along (without looking at the tell tales). The sails use the wind and also reveal how the wind is blowing. When pinching too hard, the luff will curl towards the boat. This will create a large area on the luff which is bulging in rather than out. If you are sheeted in all the way, that would mean that you are aiming as far upwind as possible (and honestly should fall off the wind a bit).

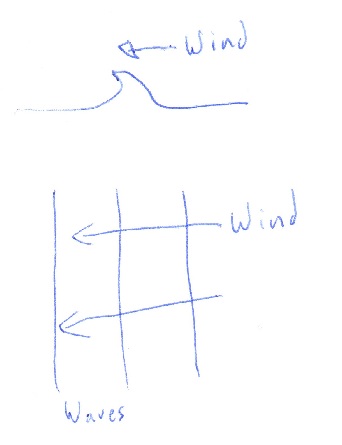

Lastly, (and my favorite way) is to read the waves. Waves are (usually) created by the wind and roll in a form perpendicular to the winds direction. This means that the waves will come at the boat 90* to the wind.

When the waves come at you from the side (beam on) this means you are on a beam reach and the wind is coming from the beam.

When beating, the waves will be coming from the front quarter, and this would indicate the wind is coming from that same direction. I don't typically read the waves when beating because the sail will begin to luff if I point too high.

Safe sailing

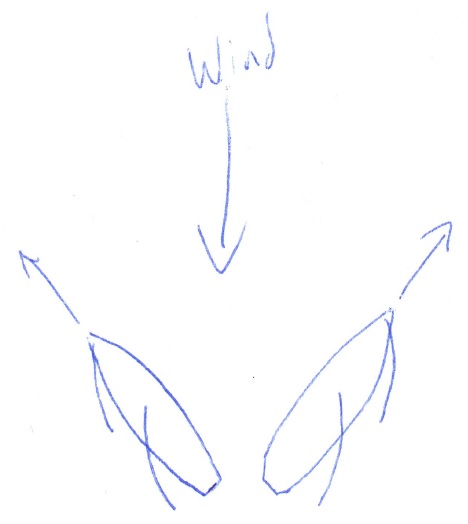

Sailing by the lee

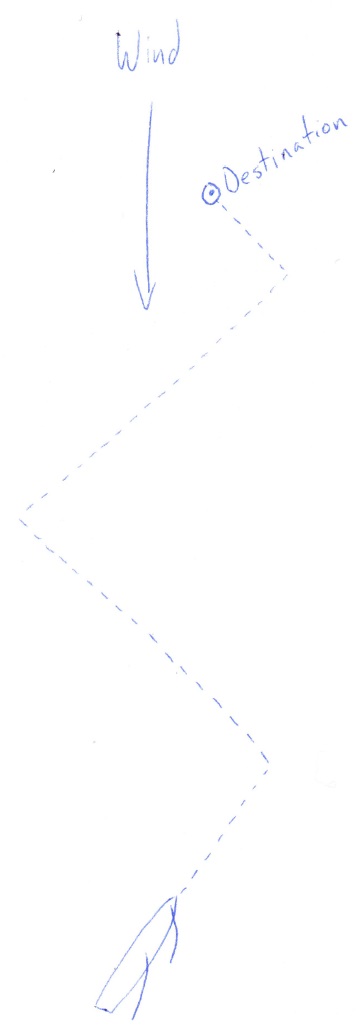

When running, this will work wonderfully and I rely on this trick more than I do my wind instruments! The waves will be coming at your stern with a slight angle. If they are perpendicular to your sides, you are on a dead run. If they are coming at your boat on the same side as your boom, you are sailing by the lee (and should rectify this immediately). If they are coming in from the side opposite to the boom, you are on a broad reach.

When sailing Wing on Wing, I make sure that the waves are perfectly perpendicular to the boat. If they change their angle slightly, I will alter course to keep the wind directly on the stern. The waves will give instant and accurate information, other methods may have a slight delay in the information delivery.

Lastly, the final reason I prefer to read the waves is it also gives you an indication of wind strength and direction off in the distance. Boat mounted wind sensors will only give you information about the wind that your boat is currently experiencing and no information about the surrounding wind. On windy days, this is not such a big deal, as there is plenty of wind to go around and keep you moving. On calm days though, reading the waves will tell you where there is wind and which way it is blowing.

On a calm day, the water will look like glass with isolated areas of ripples. These areas are where wind is present and the ripples run perpendicular to the wind. You can sail through calm areas by using these wind puffs. When you reach one, it will propel your vessel ahead. Once you leave this wind puff, you will be coasting along until you run out of momentum. By aiming to the next closest wind puff, you can actually "jump" from windy spot to windy spot.

On the opposite end of the spectrum, the waves will alert you to approaching storms. When whitecaps appear in the distance, they indicate strong wind approaching (and the need to reef your sails now). Strong storm fronts will also bring a change in wind direction and keeping an eye on the waves will tell you how to position your sails for the blast of wind that will be coming.

While none of these systems work perfectly, when used in conjunction they can help you figure out how the wind is blowing and aid your navigational decisions in plotting your desired course. Taking all the information you have available will help you sail better and safer in any wind condition.