When you are sailing along on a beautiful day and dark clouds roll in, your day is about to change. White caps will begin to crop up as the wind builds, pushing you along with a stiffer breeze. The sails will take all this wind and turn it into huge amounts of power to move your yacht through the chop! At the same time, the boat will begin to lean over much further than it was before the weather changed. What do you do now?

If you have strong rigging, capable crew, and a sea worthy vessel, you can enjoy sailing along heeled over with a rail in the water. It is very exhilarating to stand on the cockpit combings as you plow your way through the seas!

The boat won't flip from sailing heeled over very far, but it will sail much less efficiently than if it were properly trimmed. As the wind pushes you over, the sails will spill wind off the top of them as they begin to lay flat to the wind. At the same time, the keel will begin to lift out of the deep water offering less resistance towards leeway movement. The end result is the boat will lose power in its sails and begin to slide sideways as the keel loses effectiveness.

To keep the yacht more upright, the best solution is to make the sails smaller via reefing. Reefing presents less sail to the wind, which means less power generated by the sails. This might seem like it will make you move more slowly, when in fact it will do the opposite. The wind is blowing so hard that these smaller reefed sails will generate all the power you need to move through the storm conditions. Since the sails are not overpowering the sailboat anymore, the boat will stay more upright allowing the keel to work more efficiently which allows you to move forward instead of sideways.

Why does reefing work? Physics!

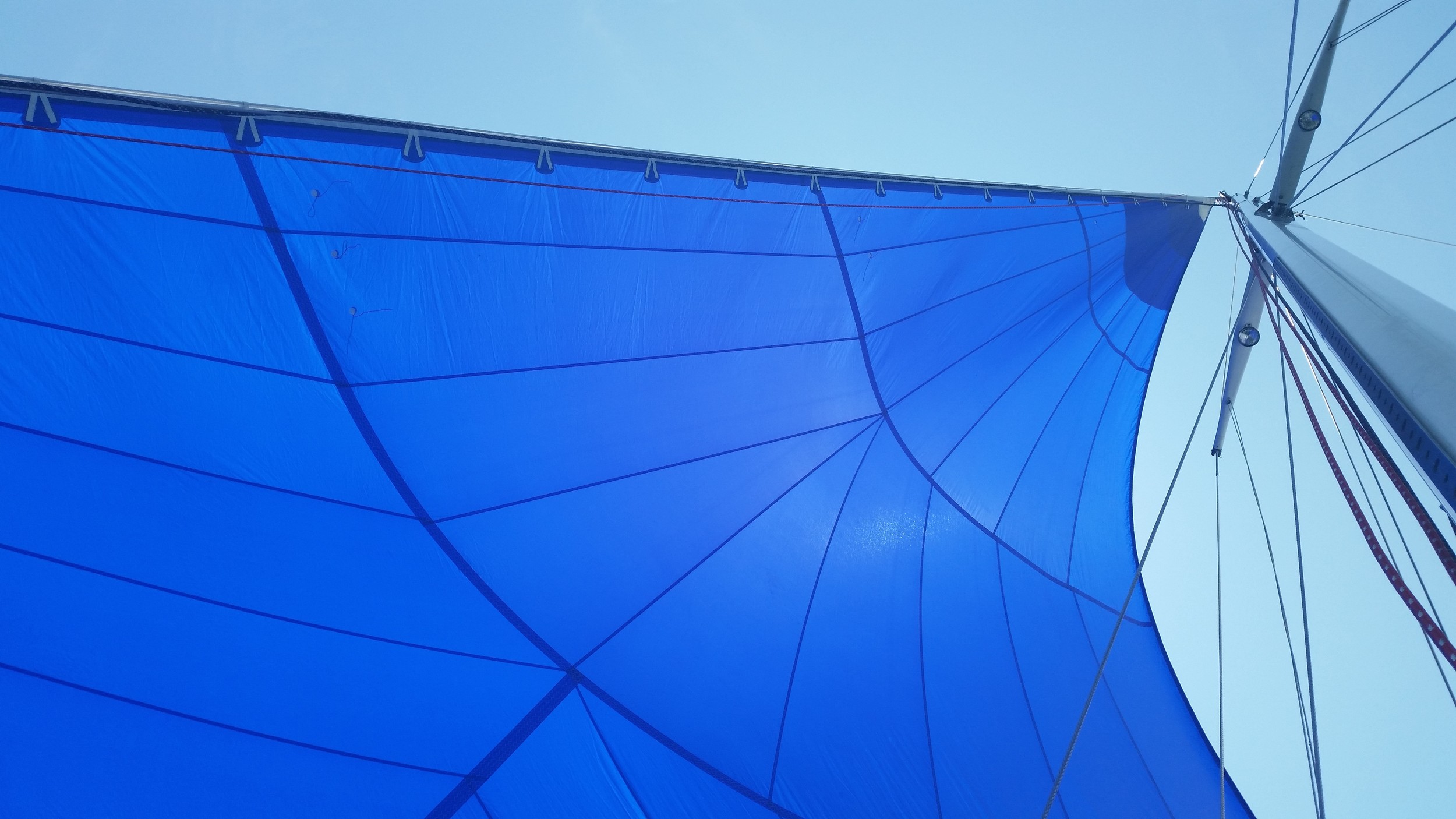

Sails present an area to the wind to form airfoils that act like wings to generate lift. This force will balance itself onto one point called the Center of Effort. This point is basically the sum of the force from the wind that is pushing on the boat. This point can be moved by trimming the sails.

If the sails are all the way up, the Center of Effort is going to be very high and will result in more heeling. If the Center of Effort is brought down, it will not have as much leverage and will result in less heeling. This point can also be moved fore and aft, depending on sail trim. If you have a jib up with no main, the Center of Effort will be forward (lee helm). If you have the main up with no jib, the Center of Effort will be aft (weather helm).

The position of the Center of Effort will have a great effect on how the helm feels. Too far forward will result in Lee Helm, too far aft will result in Weather Helm (Lee Helm turns you towards the lee, Weather Helm turns you into the weather).

When you reef your sails, the main comes down which will move the Center of Effort down and closer to the mast. When you reef the jib (or furl it up partially) you move the Center of Effort forward. This is why Cutters perform better than sloops in heavy weather. A reefed sloop will move its Center of Effort forward while a cutter will lower its jib and fly a reefed main and staysail, which moves the Center of Effort down and closer to the mast. This keeps the helm balanced and under control in heavy weather.

The take home message is: Reefing makes your sails smaller to maintain proper control of your vessel. This makes the heavy weather sailing much more comfortable and much less intimidating.